1719. A year whose memory smells of smoke. A summer of pleasant weather and determined large-scale arson along the eastern seaboard of Sweden. The year of the Russian raids.

At a huge cost in men's lives, widowed women and fatherless children, Sweden enjoyed nearly a century as a major political power around the Baltic in the 17th and early 18th centuries, under the rules of Gustavus II Adolphus, Kristina, and the Caroluses, nos X through XII. It was a little empire, still commemorated in the lyrics of the national anthem. Then it all started to unravel. Carolus XII, a psychopath who may or may not have been a military genius but whose luck had clearly run out, was killed at the siege of Fredrikssten in Norway in November 1718 at the age of 36. And the Swedish armed forces fell to pieces.

Anyone could see that the Swedish interlude on the European stage was over. Anyone except the Swedish administration, that is. At the peace talks with Peter the Great's Russia, the Swedish negotiators kept stalling for time, hoping that their war machine would get back in gear again. Peter's strategists realised that they needed to teach the Swedes a lesson. So they sent a fleet to burn almost every single building and crop along the Baltic coast of Sweden from Norrköping to Piteå, a huge distance. "

Now do you get it, guys?" They did. A peace treaty formalising Sweden's abasement was signed at Nystad in 1721.

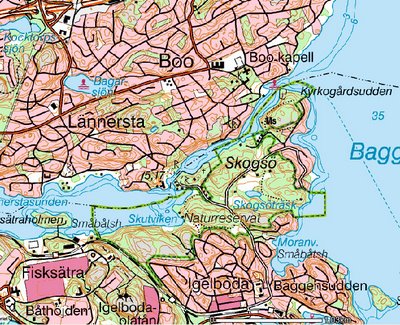

The Russian coastal fleet of 1719 had no realistic hopes of actually invading Sweden. But burning the country's coastal cities was eminently feasible. Stockholm, however, is protected by an extensive archipelago with only a few passable routes to the city. The one at Vaxholm was heavily defended. But what about Baggensstäket, the old

Viking Period entry point?

On 13 August 1719, the Russians attempted to break through provisional defences at Baggensstäket, leading to a day-long skirmish against hastily assembled second-rate Swedish troops that has gone down in history as the

Battle of Baggensstäket. Toward the evening, Swedish reinforcements arrived, and the Russians discreetly left to continue their pyromaniac activities elsewhere.

The battle was not a neat open-field affair. It was fought partly from ships, partly on land, and none of the participants are likely to have had any good overview of things. Afterwards, both the Swedes and the Russians claimed to have won, and the Swedish commanders delivered partly irreconcilable reports of what had happened, each somehow describing its author as the hero of the day. To understand the battle, we'd need objective sources.

Enter Thomas Englund and Bo Knarrström and their team from the

National Board of Antiquities' excavation unit. Having studied other battlefields of the Swedish heyday by intensive metal detecting, they are now, as I write this, pinpointing the movements of troops in the Battle of Baggensstäket.

A cool thing about this project is that although it is entirely research-driven, it has been initiated and funded by a rescue excavation unit. They have somehow managed to get around the

field-archaeological paradox. Go Bo and Thomas!

I visited them a few hours ago. It's a highly unusual site as early modern battlefields go: wooded and hilly. Much of it has been untouched woodland pasture at least since the Viking Period: indeed, some fighting has clearly taken place among the 10th century pagan graves there. Preservation is exceptionally good, although there have been rumours of detector looting in the 1980s. Musket balls, grenade splinters and spikes from the improvised wooden fortifications still lie where they ended up after the fighting. There's no money to be made from finds like these, but by looking at their technical and ballistic characteristics and their distribution across the topography, the project will be able to identify where the troops were holed up during the fighting. For those interested in individual objects, I'd say the most exciting finds so far are a 1719 Swedish copper coin and the rear end of a fine-calibre portable artillery piece that seems to have ruptured when fired.

I grew up with stories of the Battle from books and school. Now I know where they fought and what their weapons were like. When the project is done, we will be able to confront the commanders' reports with hard evidence from the battlefield.

[More blog entries about history, war, 1719, metaldetecting, battlefield, archaeology, Sweden; slagfält, metallsökare, krig, 1719, historia, arkeologi, Nacka.]